During the Middle Jurassic, Europe was characterised by continued N-S-directed extension during the continued opening of the Piemont – Liguria Ocean. This was accompanied by development of a number of sedimentary basins preserving siliciclastic infill from surrounding landmasses and calcareous sediments from carbonate platforms (Dogger Group). Bottom currents played an important role in both transport and accumulation of these sediments.

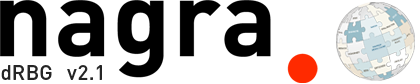

The lower division of the Middle Jurassic succession comprises the Opalinus Clay. This was deposited in the shallow epicontinental sea located between the Vindelician – Bohemian Massif in the east, the Alemannic Land to the south and the very shallow area in Burgundy to the west (Fig. 3‑8). Within the shallow epicontinental sea deeper areas are referred as "shallow mid epicontinental". The accommodation space needed to deposit the compacted ca. 100 m thick unit of Opalinus Clay in relatively shallow water – especially considering uncompacted sediment thicknesses – was provided by regional subsidence (Wetzel & Allia 2003). High siliciclastic input from the Alemannic Land, the Vindelician – Bohemian Massif or landmasses even further to the northeast led to deposition of mostly claystone with varying contents of silt and fine sand over the entire Northern Switzerland (Lauper et al. 2021b, Zimmerli et al. 2024). This environment resulted in the deposition of the relatively homogeneous facies of the Opalinus Clay with little lateral variability compared with other Mesozoic formations of Northern Switzerland. Within the Opalinus Clay, a shallowing-upward trend, with increased silt and fine sand contents towards the top, is thought to reflect an overall regression (Zimmerli et al. 2024). Towards the top of the formation, reduced sedimentation is recorded by calcareous, partly iron-rich beds intercalated in claystone, which can be correlated on a local to regional scale (Wohlwend et al. 2024).

The overlying succession, Dogger Group above Opalinus Clay, preserves more lateral variability and complexity. A first phase of deposition largely comprises siltstone, claystone and argillaceous marl (Passwang Formation and its time equivalents in the east). However, local metre-scale beds or bedded intervals of sandy, bioclastic and biomicritic limestone were also deposited. Additionally, during episodes of reduced deposition, iron-rich, decimetre- to metre-scale beds, including iron-oolites were deposited. These sediments locally preserve cycles of claystone overlain by sandy and/or bioclastic marl, limestone and, finally, iron-oolitic beds. These cycles may represent shallowing-upward trends related to sea-level variations (Burkhalter 1996) and/or climate variability. The preservation of cycles is laterally highly variable, thought to be in response to local variations in bathymetry with local swells and depressions in combination with sediment transport by bottom currents. Such bottom currents may have locally (i.e. at the present location of NL) deposited a several-km-scale, clay-mineral-rich sediment drift. On top of this positive relief, an isolated carbonate platform consisting of mostly coral and bioclastic limestone developed («Herrenwis Unit»; Ruchat et al. 2024).

Fig. 3‑8:Palaeogeographic situation of Western to Central Europe in the Aalenian during the sedimentation of the Opalinus Clay and its time equivalents

The red rectangle shows the extent of the detailed palaeoenvironment maps (Section 4.2). Map based on Etter (1990) and Lauper et al. (2021a). The north arrow refers to present-day geographic north. The approximate locations of the cities are shown to simplify orientation.

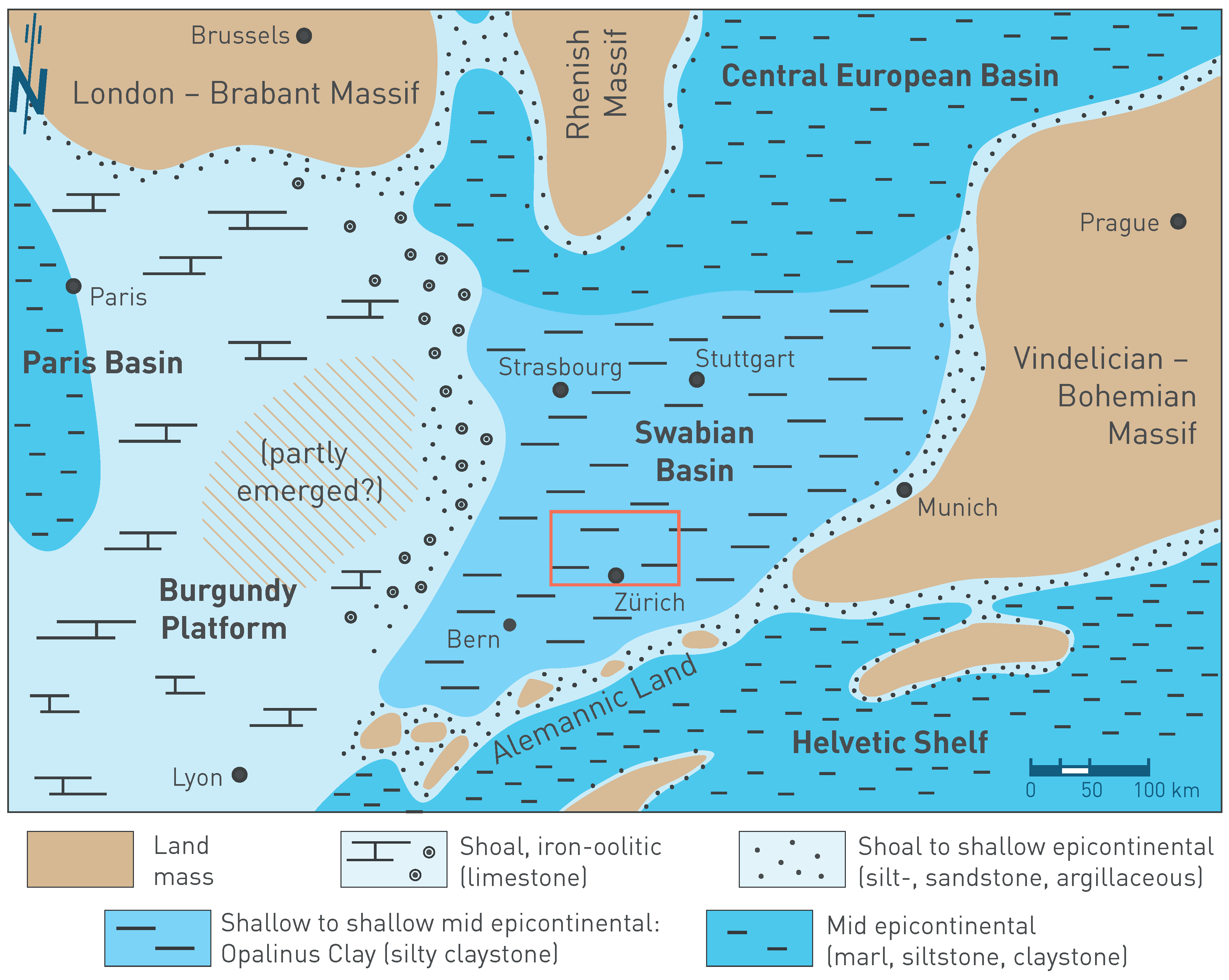

In a second phase of deposition, the Celtic Platform extended into Northern Switzerland and oolitic and bioclastic limestone interbedded with some more marly interlayers (Hauptrogenstein) (Fig. 3‑9) were deposited in a shallow marine environment. Towards the Swabian Basin in the east calcareous marl with interfingering oolitic limestone prevailed (Klingnau Formation) while argillaceous marl, siltstone and claystone dominated further offshore («Parkinsoni-Württembergica-Schichten»). In NL, these sediments, probably in the form of sediment drifts, filled the basin and finally also covered the isolated carbonate platform, so that the «Herrenwis Unit» is embedded in clay-mineral-rich sedimentary rocks. The third phase of deposition is again characterised by a condensed succession of often fossiliferous, iron-oolitic marl and limestone (mostly Ifenthal and Wutach Formations; Bitterli-Dreher 2012, Bläsi et al. 2013).

Fig. 3‑9:Palaeogeographic situation of Western to Central Europe in the Bajocian during the sedimentation of the Hauptrogenstein and «Parkinsoni-Württembergica-Schichten» and their time equivalents

The red rectangle shows the extent of the detailed palaeoenvironment maps (Section 4.2). Map based on Barron et al. (2012), Correia (2018), Geyer et al. (2023), Gonzalez & Wetzel (1996), Krakow & Schunke (2017), Munier et al. (2021) and Védrine & Strasser (2009). The north arrow refers to present-day geographic north. The approximate locations of the cities are shown to simplify orientation.